PLAY AUDIO

Text: Jelle Steenbergen | Photography: David Kaszlikowski (verticalvision.pl)

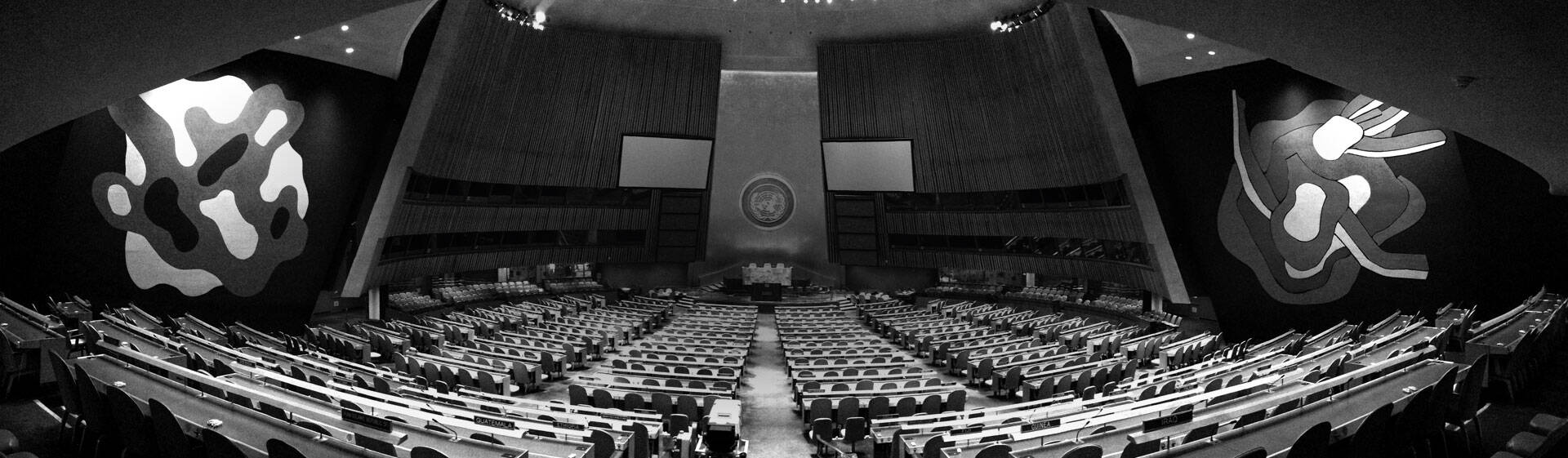

Many of Tjukiji’s vendors, who have occupied the same near sacred –to them – spot for generations, argue that to move is to destroy the identity of the hallowed market. The blood, sweat, and fish guts have intertwined with the men and women working there to create something unique in a way that can’t be found anywhere else. The case of Tsukiji has an emotional appeal as strong as the Badjao, but why?

There is no type of food that has a better story than fish. Fishing has all the adventure of the hunt, all the romance and hardship of the farm, and a sense of history and nostalgia you find nowhere else. From the ancient mariner to the old man and the sea, fish embodies all the vital things that lie beyond the plate.

My opinion is that if we were to lose fish, we would lose not just a food group or an inspirational story, we would lose our connection with a vital part of the natural world. Eating fish is a visceral and tangible reminder that we are part of a larger whole. An entire planet that we need to cherish and protect. In the case of vegetables, or meat, we can visit the forests or farms. We can see, hear, and feel the signature of time and place there. But with the sea it is not so simple. She is as shrouded as she ever was, as impenetrable. We know more about the surface of the moon than the depths of the ocean. Her creatures are the only reliable way we have to know how she is doing. There would be no greater tragedy than to lose that one, irreplaceable means of communication.

Fish matters. We need to start acting like it.

I realize the irony of the previous paragraph. Isn’t that exactly what I’m doing right now? Telling you how to feel about the possibility that our food system might be irreparably damaging ecosystems, and maybe even destroying cultures? Why should you listen to me? My hope is only to make you aware of the problem, to show you all the beauty and inspiration we are in danger of losing. I cannot decide for you if the sacrifice is worthwhile, only point out that if we continue as we are, we are robbing future generations of that choice.

and long for fish; go home

and weave a net.”

with an everlasting itch for

things remote. I love to sail

forbidden seas, and land on

barbarous coasts.”

We live in an age I’ve heard described as exponential. Change happens faster than any of us can track, let alone adapt to. Everything, everywhere feels like it’s growing more complex and intricate by the day. Is it any wonder that we seek simplicity, authenticity, and transparency? An increasing number of us turn to our food as a means of reconnection. A restoration of bonds not just between people, but between a person and the world at large. It’s so easy to lose track of oneself and one’s place in the world when an endless, unceasing stream of information is our constant companion. This is compounded by the fact that so many factors seem to prey on that disconnected insecurity. They seem to say: ‘Don’t worry, we’ll tell you what to think, what to feel, what to buy.’

The allure is undeniable, and the harsh, physical reality of waterbound life (at least as it was in the past) combines with it to breed a sense of community and unity that is inimitable. The weight of history only serves to strengthen these already unbreakable bonds. Is there a more romanticized figure than the fisherman? I’d argue there isn’t, and that’s exactly why fish are perhaps the most important food we have in our modern times. Modern times wherein the focus of our food has long since stopping being the factual flavors, textures, and aromas, to land instead on the narrative, heritage, and intangible meaning of the things we eat. And in this area, fish is unbeatable.

for the secret of the sea,

and the heart of the great

ocean sends a thrilling

pulse through me.”

Libraries have been filled with words about humanity and the unending love/hate relationship we have with the sea. The sea is nature at her most cruel, most mysterious, and most compassionate. Her bounties are unrivaled, her wrath equally so. To be taken in by the tales of oceans vast and waters rough is a temptation that’s been difficult to resist for as long as there have been warm and dry places to tell stories. The Badjao people feel it strongly, as do the vendors at Tsukiji, and, perhaps, you: the call of the sea, and the creatures in it.

A world without fish would be a poorer world, a diminished world. If our current system were to continue unabated and uncontested, then it will inevitably spell the end for rich and vibrant cultures like the Badjao. Admittedly, theirs is a photogenic case, a case with an easy emotional appeal, but the interesting notion is that when it comes to fish, every case is like theirs. Take, for example, Tokyo’s much-maligned Tsukiji fish market. The fish market’s location is prime real estate. Real estate that, according to many, could be better used for other, more profitable ventures.

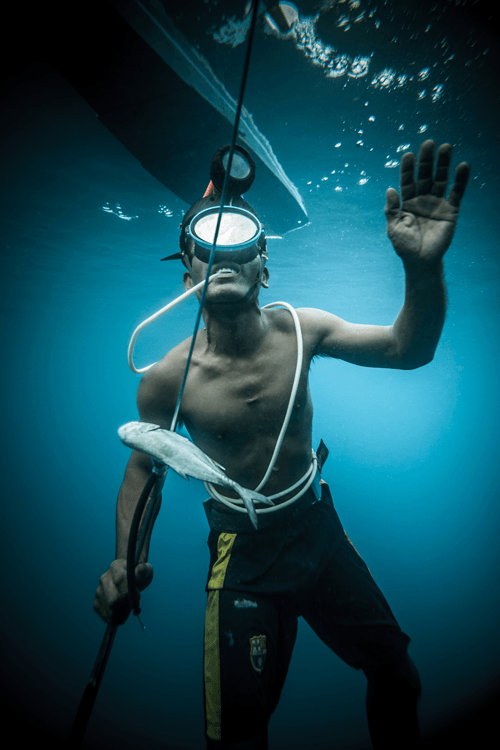

Look at, for example, the enthralling existence of the Badjoa tribe in Asia. They are a tribe of sea-nomads that live their lives in boats or stilt houses, and spend nearly every waking moment in the water, diving for food or other useful items. The sea is their home more than the land will ever be, and their way of life is threatened by modernity’s callous disrespect. This is a bold claim to make, perhaps, but an important one. It’s old news that the world’s oceans aren’t doing well, and the cry that some day soon we might not have any fish left to eat has long since shifted from alarmist prophecy to frighteningly real possibility. It only takes a single look at these stunning photographs of the Badjao tribe to realize that when we do, we’ll lose much more than a tasty source of food.

aloud, "I'll stay with

you until I am dead.”

PLAY AUDIO

My opinion is that if we were to lose fish, we would lose not just a food group or an inspirational story, we would lose our connection with a vital part of the natural world. Eating fish is a visceral and tangible reminder that we are part of a larger whole. An entire planet that we need to cherish and protect. In the case of vegetables, or meat, we can visit the forests or farms. We can see, hear, and feel the signature of time and place there. But with the sea it is not so simple. She is as shrouded as she ever was, as impenetrable. We know more about the surface of the moon than the depths of the ocean. Her creatures are the only reliable way we have to know how she is doing. There would be no greater tragedy than to lose that one, irreplaceable means of communication.

Fish matters. We need to start acting like it.

with an everlasting itch for

things remote. I love to sail

forbidden seas, and land on

barbarous coasts.”

I realize the irony of the previous paragraph. Isn’t that exactly what I’m doing right now? Telling you how to feel about the possibility that our food system might be irreparably damaging ecosystems, and maybe even destroying cultures? Why should you listen to me? My hope is only to make you aware of the problem, to show you all the beauty and inspiration we are in danger of losing. I cannot decide for you if the sacrifice is worthwhile, only point out that if we continue as we are, we are robbing future generations of that choice.

The allure is undeniable, and the harsh, physical reality of waterbound life (at least as it was in the past) combines with it to breed a sense of community and unity that is inimitable. The weight of history only serves to strengthen these already unbreakable bonds. Is there a more romanticized figure than the fisherman? I’d argue there isn’t, and that’s exactly why fish are perhaps the most important food we have in our modern times. Modern times wherein the focus of our food has long since stopping being the factual flavors, textures, and aromas, to land instead on the narrative, heritage, and intangible meaning of the things we eat. And in this area, fish is unbeatable.

for the secret of the sea,

and the heart of the great

ocean sends a thrilling

pulse through me.”

We live in an age I’ve heard described as exponential. Change happens faster than any of us can track, let alone adapt to. Everything, everywhere feels like it’s growing more complex and intricate by the day. Is it any wonder that we seek simplicity, authenticity, and transparency? An increasing number of us turn to our food as a means of reconnection. A restoration of bonds not just between people, but between a person and the world at large. It’s so easy to lose track of oneself and one’s place in the world when an endless, unceasing stream of information is our constant companion. This is compounded by the fact that so many factors seem to prey on that disconnected insecurity. They seem to say: ‘Don’t worry, we’ll tell you what to think, what to feel, what to buy.’

and long for fish; go home

and weave a net.”

A world without fish would be a poorer world, a diminished world. If our current system were to continue unabated and uncontested, then it will inevitably spell the end for rich and vibrant cultures like the Badjao. Admittedly, theirs is a photogenic case, a case with an easy emotional appeal, but the interesting notion is that when it comes to fish, every case is like theirs. Take, for example, Tokyo’s much-maligned Tsukiji fish market. The fish market’s location is prime real estate. Real estate that, according to many, could be better used for other, more profitable ventures.

Many of Tjukiji’s vendors, who have occupied the same near sacred –to them – spot for generations, argue that to move is to destroy the identity of the hallowed market. The blood, sweat, and fish guts have intertwined with the men and women working there to create something unique in a way that can’t be found anywhere else. The case of Tsukiji has an emotional appeal as strong as the Badjao, but why?

Libraries have been filled with words about humanity and the unending love/hate relationship we have with the sea. The sea is nature at her most cruel, most mysterious, and most compassionate. Her bounties are unrivaled, her wrath equally so. To be taken in by the tales of oceans vast and waters rough is a temptation that’s been difficult to resist for as long as there have been warm and dry places to tell stories. The Badjao people feel it strongly, as do the vendors at Tsukiji, and, perhaps, you: the call of the sea, and the creatures in it.

Look at, for example, the enthralling existence of the Badjoa tribe in Asia. They are a tribe of sea-nomads that live their lives in boats or stilt houses, and spend nearly every waking moment in the water, diving for food or other useful items. The sea is their home more than the land will ever be, and their way of life is threatened by modernity’s callous disrespect. This is a bold claim to make, perhaps, but an important one. It’s old news that the world’s oceans aren’t doing well, and the cry that some day soon we might not have any fish left to eat has long since shifted from alarmist prophecy to frighteningly real possibility. It only takes a single look at these stunning photographs of the Badjao tribe to realize that when we do, we’ll lose much more than a tasty source of food.

aloud, "I'll stay with

you until I am dead.”

There is no type of food that has a better story than fish. Fishing has all the adventure of the hunt, all the romance and hardship of the farm, and a sense of history and nostalgia you find nowhere else. From the ancient mariner to the old man and the sea, fish embodies all the vital things that lie beyond the plate.