"We now have three farms in the Netherlands. In the United States, four more Kipster farms will open this year in Indiana. These are exact copies of the farm model we have in the Netherlands. Our commercial supermarket partner in the U.S. is Kroger, the largest supermarket after Walmart. The expansion of Kipster will follow in various European countries in the coming years. Our team is ready; we have hired a general manager with experience in international growth and a new commercial director. We want to take Kipster around the world to show that things can be done differently. My grandfather already knew that a circular system was the best way for the planet and our animals. 80 years ago he didn't do anything else. We have forgotten how to do it. That's why with Kipster, we are moving forward to the past.”

Our team is ready to grow our business in the United States, as well as in various European countries

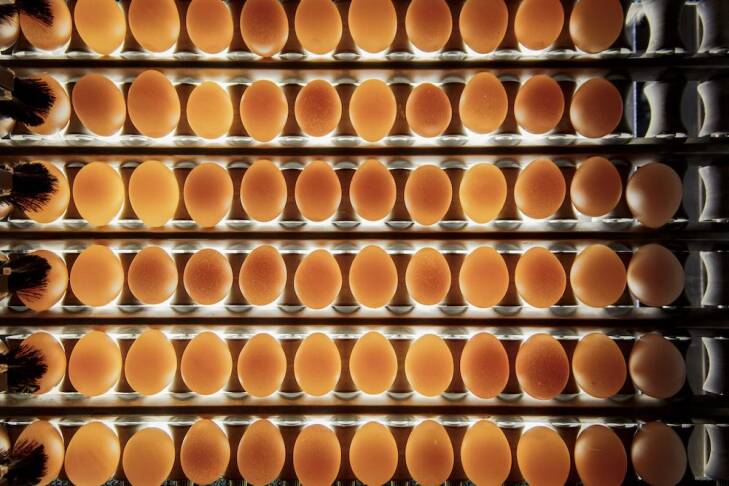

"Because of the 1100 solar panels on our roof, we are self-sufficient in terms of energy. Transparency towards the consumer is very important to us, so our door is always open to visitors. We have a permanent company presentation running in which we explain how we work. For example, we have white chickens because a white egg has a 5% lower carbon footprint than a brown egg. 70% of the carbon footprint of an egg depends on the feed. By using waste streams for our chicken feed, we reduce emissions by 50%. We want to have as low a carbon footprint as possible and we compensate for the shortfall with carbon credits. Another very important aspect is that we have been able to conclude contracts with companies that believe in our concept. In the Netherlands, the supermarket chain Lidl and the food service purchasing organization Victoria Trading have guaranteed the purchase of all our eggs for a minimum of five years."

"For all these reasons, I started Kipster with three others in 2013; the first Kipster farm opened in 2017. We are still the only commercial laying poultry farm that only feeds its chickens with food that we as humans can no longer or don't want to eat, such as stale bread. We turn it into chicken feed, which is a challenge because human food is too salty. In Europe, ninety million tons of food waste is available annually to make feed from; only five million tons are used, so there is still a lot of potential. You can certainly process food waste in other, better, ways, such as donating it to the food bank. But you can also do much worse things with it, such as disposing it in the landfill. It depends on the quality, but feeding animals is a seriously good use for a lot of food waste.”

“Hannah van Zanten's observation that animals still have a role in a circular food system gave us the scientific encouragement to develop Kipster. Subsequently, animal welfare became the main pillar in our business. I studied intelligence, emotional life and emotions in animals. I learnt that a pig’s emotions, for example, are 80% similar to the emotions of a human being. So there is sadness when you take away a child from them or when you lock them up in a cage. For our chickens, we try to ensure the best possible welfare. Therefore, we have recreated a natural environment with bushes, lots of variety, daylight and also fresh outdoor air inside. There is plenty of room around the farm. Our male chickens are not considered an undesired by-product and therefore gassed when they’re only day-old chicks, but raised on an organic farm and slaughtered and processed as a meat product after fourteen weeks."

In developing Kipster, animal welfare became the main pillar of our business

"I was looking for scientific evidence. Through Wageningen University and Research (WUR), I ended up connecting with Hannah van Zanten who has a PhD in circular food systems and the feed-food dilemma. Her vision is the following: 70% of all farmland we use for animals and 30% of all grains we produce we give to animals. This leads to a so-called feed-food competition, in which people and animals compete for food and natural resources such as land or water. The key challenge in the coming decades, in her view, will be to produce enough safe and nutritious food for future populations without running out of resources or destroying the Earth's ecosystems. In other words, without exhausting the biological and physical resources of the planet. A key question in feeding the future population therefore is: ‘what is the role of farm animals in a sustainable food system?’”

“There are two types of soils in the world: fertile and marginal. Fertile soils are suitable for the production of vegetable crops. Marginal lands are not suitable for that; you can however, let animals graze on it. If you use the residual streams from the fertile soils to feed animals and use those animal proteins to supplement plant-based food for people, then the earth keeps itself in balance. That's the philosophy Kipster is built on, on that circular idea."

How ethical is it to feed good raw materials suitable for human consumption to breed animals?

“I started talking to supermarkets, but most were only interested in one thing: the lowest price. Then I turned to politicians, but that too was difficult because there was hardly any long-term vision. I then started talking to civil society organizations, NGOs like the Animal Protection Society and Stichting Wakker Dier in the Netherlands and later the ASPCA (American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, ed.) in the United States; I noticed they set plans for 20 to 30 years forward. They look much further ahead and there is more scientific evidence behind it than I had ever thought. That didn't mean it was easy to get their support, because their view on farmers is very critical. But I wanted to learn; if there is research showing that I can become an even more sustainable and animal-friendly chicken farmer, I will listen to their advice.”

“The turning point came in 2013. I had a delegation visiting from Africa who wanted to learn about the efficient Dutch poultry sector. When I advised that chickens needed good feed such as maize, they asked me if I was out of my mind. Why do you feed corn to chickens? We give that to our people! They went on to say: “It is actually inefficient what you do in the rich West. From a kilo of corn or grain we can feed ten people. You feed the same amount to chickens or pigs, which then can only feed four people. That insight was an eye opener. I learned from them instead of the other way round. The Dutch are among the best farmers in the world, we can make as much animal protein as possible from a kilo of grain, but the question I was asked was whether our system is correct. Their story made me doubt it. And I sincerely wondered how ethical it is to give good raw materials suitable for human consumption to specially breed animals, when you know that a billion people are starving in the world."

At the peak, we were breeding 8 million chicks per year

“Together with my brother, I took over the company in 1998 after studying agricultural economics at Wageningen University. I had three core values that were important: large-scale, large-scale and large-scale. At the peak, we were breeding 8 million chicks, we had stakes in several European poultry companies and a turnover of 45 million euro. All in all, that made us big farmers. But we grew too fast and the bird flu in 2003 was fatal to us: we went bankrupt. At the time I was 34 years old, my bank balance was zero and I had to start all over again.”

"It gave me time to think. Did we go too far in the system of producing as much as possible at the lowest possible cost? Consumer behavior changed and so had the idea of how we should deal with the world. Although, for the most part, intensive livestock farming is still focused on that goal of producing a lot for little. I decided that I wanted to remain active in poultry farming, but with different core values: people-friendly, animal-friendly, environment-friendly. The question was: would I be able to make a living with those values?”

“If that’s the mission, there are only two paths for a farm: specialization and scaling up. So my father got rid of the cows and pigs and continued with just chickens. He was going to produce as many eggs as possible at the lowest possible cost. In the 1970s, battery cages were introduced in Europe from America. This system was adopted en masse, but because there were major drawbacks – deteriorating animal welfare, harmful environmental effects and cut-throat competition on price – the batteries were exchanged for a free-range system. My father went along with this trend and became one of the largest chicken farmers in the south of the Netherlands.”

After World War II the goal of the agricultural sector was to produce as much food as possible at the lowest possible cost

Ruud Zanders likes to talk about his parents and ancestors, who were farmers in the Netherlands. Using family history, he illustrates the major changes in agriculture over the last 60 years.

"My mom is 80 years old now. She grew up on a small mixed farm with some chickens, pigs and cows; many farms during the last century were like that in the Netherlands. She had eight siblings. You can hardly imagine it, but there was a long dining table in the dining room with a fence on one side, and behind it was the quarters of their pig. When a cauliflower was cut, the leaves went straight over the fence to the pig. As for any other leftovers. After a year, when the pig was fat enough it was slaughtered. It called for a farm feast. The pig was eaten over the course of six months to a year.”

“My dad is 80 years old as well, and his parents also had a small mixed farm. His family consisted of eleven children; he had one brother and nine sisters. My dad took over the business with his brother, but times changed. World War II had just ended and there was a lot of hunger. With aid from the Marshall Plan, Europe was being rebuilt. In the Netherlands there was a visionary Minister of Agriculture – Sicco Mansholt – who made a plan in which ‘Nooit meer honger’ – Hunger, never again – became the focus point. The goal of the agricultural sector was to produce as much food as possible at the lowest possible cost. The belief was that if there was enough food available and everyone was able to buy food, Europe would no longer fall prey to war. Therefore, my father's only mission was, how can we produce as much food as possible at the lowest possible cost.”

Hans Steenbergen Nina Slagmolen Xiao Er Kong

Kipster, a Dutch company, claims to be the most animal, environment, and human friendly chicken farm in the world. Kipster’s main focus isn’t the production of as many eggs as possible, but a circular agriculture without any negative consequences for people, animals and the planet. The innovative concept started in 2017 and is expanding to the United States this year. Food Inspiration spoke with one of the founders, chicken farmer Ruud Zanders.

Kipster:

A happy chicken lays climate neutral eggs

interview

9 min

"We now have three farms in the Netherlands. In the United States, four more Kipster farms will open this year in Indiana. These are exact copies of the farm model we have in the Netherlands. Our commercial supermarket partner in the U.S. is Kroger, the largest supermarket after Walmart. The expansion of Kipster will follow in various European countries in the coming years. Our team is ready; we have hired a general manager with experience in international growth and a new commercial director. We want to take Kipster around the world to show that things can be done differently. My grandfather already knew that a circular system was the best way for the planet and our animals. 80 years ago he didn't do anything else. We have forgotten how to do it. That's why with Kipster, we are moving forward to the past.”

"Because of the 1100 solar panels on our roof, we are self-sufficient in terms of energy. Transparency towards the consumer is very important to us, so our door is always open to visitors. We have a permanent company presentation running in which we explain how we work. For example, we have white chickens because a white egg has a 5% lower carbon footprint than a brown egg. 70% of the carbon footprint of an egg depends on the feed. By using waste streams for our chicken feed, we reduce emissions by 50%. We want to have as low a carbon footprint as possible and we compensate for the shortfall with carbon credits. Another very important aspect is that we have been able to conclude contracts with companies that believe in our concept. In the Netherlands, the supermarket chain Lidl and the food service purchasing organization Victoria Trading have guaranteed the purchase of all our eggs for a minimum of five years."

Our team is ready to grow our business in the United States, as well as in various European countries

"For all these reasons, I started Kipster with three others in 2013; the first Kipster farm opened in 2017. We are still the only commercial laying poultry farm that only feeds its chickens with food that we as humans can no longer or don't want to eat, such as stale bread. We turn it into chicken feed, which is a challenge because human food is too salty. In Europe, ninety million tons of food waste is available annually to make feed from; only five million tons are used, so there is still a lot of potential. You can certainly process food waste in other, better, ways, such as donating it to the food bank. But you can also do much worse things with it, such as disposing it in the landfill. It depends on the quality, but feeding animals is a seriously good use for a lot of food waste.”

“Hannah van Zanten's observation that animals still have a role in a circular food system gave us the scientific encouragement to develop Kipster. Subsequently, animal welfare became the main pillar in our business. I studied intelligence, emotional life and emotions in animals. I learnt that a pig’s emotions, for example, are 80% similar to the emotions of a human being. So there is sadness when you take away a child from them or when you lock them up in a cage. For our chickens, we try to ensure the best possible welfare. Therefore, we have recreated a natural environment with bushes, lots of variety, daylight and also fresh outdoor air inside. There is plenty of room around the farm. Our male chickens are not considered an undesired by-product and therefore gassed when they’re only day-old chicks, but raised on an organic farm and slaughtered and processed as a meat product after fourteen weeks."

In developing Kipster, animal welfare became the main pillar of our business

"I was looking for scientific evidence. Through Wageningen University and Research (WUR), I ended up connecting with Hannah van Zanten who has a PhD in circular food systems and the feed-food dilemma. Her vision is the following: 70% of all farmland we use for animals and 30% of all grains we produce we give to animals. This leads to a so-called feed-food competition, in which people and animals compete for food and natural resources such as land or water. The key challenge in the coming decades, in her view, will be to produce enough safe and nutritious food for future populations without running out of resources or destroying the Earth's ecosystems. In other words, without exhausting the biological and physical resources of the planet. A key question in feeding the future population therefore is: ‘what is the role of farm animals in a sustainable food system?’”

“There are two types of soils in the world: fertile and marginal. Fertile soils are suitable for the production of vegetable crops. Marginal lands are not suitable for that; you can however, let animals graze on it. If you use the residual streams from the fertile soils to feed animals and use those animal proteins to supplement plant-based food for people, then the earth keeps itself in balance. That's the philosophy Kipster is built on, on that circular idea."

How ethical is it to feed good raw materials suitable for human consumption to breed animals?

“I started talking to supermarkets, but most were only interested in one thing: the lowest price. Then I turned to politicians, but that too was difficult because there was hardly any long-term vision. I then started talking to civil society organizations, NGOs like the Animal Protection Society and Stichting Wakker Dier in the Netherlands and later the ASPCA (American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, ed.) in the United States; I noticed they set plans for 20 to 30 years forward. They look much further ahead and there is more scientific evidence behind it than I had ever thought. That didn't mean it was easy to get their support, because their view on farmers is very critical. But I wanted to learn; if there is research showing that I can become an even more sustainable and animal-friendly chicken farmer, I will listen to their advice.”

“The turning point came in 2013. I had a delegation visiting from Africa who wanted to learn about the efficient Dutch poultry sector. When I advised that chickens needed good feed such as maize, they asked me if I was out of my mind. Why do you feed corn to chickens? We give that to our people! They went on to say: “It is actually inefficient what you do in the rich West. From a kilo of corn or grain we can feed ten people. You feed the same amount to chickens or pigs, which then can only feed four people. That insight was an eye opener. I learned from them instead of the other way round. The Dutch are among the best farmers in the world, we can make as much animal protein as possible from a kilo of grain, but the question I was asked was whether our system is correct. Their story made me doubt it. And I sincerely wondered how ethical it is to give good raw materials suitable for human consumption to specially breed animals, when you know that a billion people are starving in the world."

“Together with my brother, I took over the company in 1998 after studying agricultural economics at Wageningen University. I had three core values that were important: large-scale, large-scale and large-scale. At the peak, we were breeding 8 million chicks, we had stakes in several European poultry companies and a turnover of 45 million euro. All in all, that made us big farmers. But we grew too fast and the bird flu in 2003 was fatal to us: we went bankrupt. At the time I was 34 years old, my bank balance was zero and I had to start all over again.”

"It gave me time to think. Did we go too far in the system of producing as much as possible at the lowest possible cost? Consumer behavior changed and so had the idea of how we should deal with the world. Although, for the most part, intensive livestock farming is still focused on that goal of producing a lot for little. I decided that I wanted to remain active in poultry farming, but with different core values: people-friendly, animal-friendly, environment-friendly. The question was: would I be able to make a living with those values?”

At the peak, we were breeding 8 million chicks per year

“If that’s the mission, there are only two paths for a farm: specialization and scaling up. So my father got rid of the cows and pigs and continued with just chickens. He was going to produce as many eggs as possible at the lowest possible cost. In the 1970s, battery cages were introduced in Europe from America. This system was adopted en masse, but because there were major drawbacks – deteriorating animal welfare, harmful environmental effects and cut-throat competition on price – the batteries were exchanged for a free-range system. My father went along with this trend and became one of the largest chicken farmers in the south of the Netherlands.”

After World War II the goal of the agricultural sector was to produce as much food as possible at the lowest possible cost

Ruud Zanders likes to talk about his parents and ancestors, who were farmers in the Netherlands. Using family history, he illustrates the major changes in agriculture over the last 60 years.

"My mom is 80 years old now. She grew up on a small mixed farm with some chickens, pigs and cows; many farms during the last century were like that in the Netherlands. She had eight siblings. You can hardly imagine it, but there was a long dining table in the dining room with a fence on one side, and behind it was the quarters of their pig. When a cauliflower was cut, the leaves went straight over the fence to the pig. As for any other leftovers. After a year, when the pig was fat enough it was slaughtered. It called for a farm feast. The pig was eaten over the course of six months to a year.”

“My dad is 80 years old as well, and his parents also had a small mixed farm. His family consisted of eleven children; he had one brother and nine sisters. My dad took over the business with his brother, but times changed. World War II had just ended and there was a lot of hunger. With aid from the Marshall Plan, Europe was being rebuilt. In the Netherlands there was a visionary Minister of Agriculture – Sicco Mansholt – who made a plan in which ‘Nooit meer honger’ – Hunger, never again – became the focus point. The goal of the agricultural sector was to produce as much food as possible at the lowest possible cost. The belief was that if there was enough food available and everyone was able to buy food, Europe would no longer fall prey to war. Therefore, my father's only mission was, how can we produce as much food as possible at the lowest possible cost.”

Ruud Zanders expands to the US with his revolutionary chicken farm.

Kipster: A happy chicken lays climate neutral eggs

Hans Steenbergen Nina Slagmolen Xiao Er Kong

Kipster, a Dutch company, claims to be the most animal, environment, and human friendly chicken farm in the world. Kipster’s main focus isn’t the production of as many eggs as possible, but a circular agriculture without any negative consequences for people, animals and the planet. The innovative concept started in 2017 and is expanding to the United States this year. Food Inspiration spoke with one of the founders, chicken farmer Ruud Zanders.

9 min