What’s the goal?

Founder of True Price Michel Scholte: “The goal isn’t to charge higher prices. The goal is to develop products with a lower societal and environmental cost.” Asking consumers to pay more for the same product is a tough sell in the best of times, and we are not in the best of times. With food inequality on the rise due to the COVID-19 pandemic, asking consumers to pay a true price is beyond the means of many.

Continuing to be willfully ignorant of external costs will, however, lead to more problems down the road. The process of internalizing these external costs may be long and painful, and the brunt of the burden will need to be carried by those that have the means to do so. Corporations have begun to pivot towards a broader purpose, in which they are no longer beholden to shareholder value above everything. True price calculations should be part of this new wave and definition of economic growth. The hard reality is that short term profits will need to be sacrificed for long term gains, and that if you can afford to do so, you should consider paying a little more for the food you love, so that the people that can’t might be able to in the future.

True Price Michel Scholte

Example of True Price calculation

Retail price for a chocolate bar of 100 grams: 1,45 dollars

True Price: 1.94 dollars

The difference of 0,49 dollars between retail price and True Price is mainly caused by the unfair wages of coffee farmers (social price) and pollution from transport (natural price).

Retail price a liter of milk from a Dutch farmer: 1.39 dollars

True Price: 1,69 dollars

The difference of 0.30 cents caused partially by low wages and the unfair competitive position of supermarkets in comparison to farmers in the Netherlands (social price). For the most part the difference between True Price and retail price is caused by the price of land use and emissions caused cows (natural price).

It should be noted that these methods are far from complete or comprehensive. Further research and modeling is needed to ensure a more accurate reflection of reality.

Restoration costs. These are the costs of bringing people’s health, wealth, circumstances, capabilities, or environmental stocks and environmental qualities to the state they would have been in the absence of the social and environmental damage associated with an impact. Replanting a forest would be an example, as would raising the wages of workers to a fair living standard.

Compensation costs. These are applied when the social or economic damage of an impact is severe or long lasting enough to require compensation. To continue with the example above, these would include back-pay for the workers, and expanding replanting efforts to compensate for the carbon absorption lost from deforestation.

Prevention of recurrence costs. These represent the costs that would be incurred in the future to avoid, avert or prevent the identified social and environmental impacts of a product from occurring again. For example putting an independent analyst in place to prevent human rights breaches from occuring again, or similarly a forestry service or other protective measures.

Retribution costs. The costs associated with fines, sanctions or penalties imposed by governments for certain violations of legal or widely accepted obligations. They represent the damage to society caused by breaking the law.

The question that then rises is how to calculate these significant and broad external costs? Sticking with the methods used by the True Price foundation they identify four different principles to include in their monetization factors, taken from the comprehensive paper released by the True Price Foundation:

© Chantal Arnts

Koeckebackers

The retail price is the price we’re used to paying, and takes into account the economic and market forces, as well as traditional profit margins.

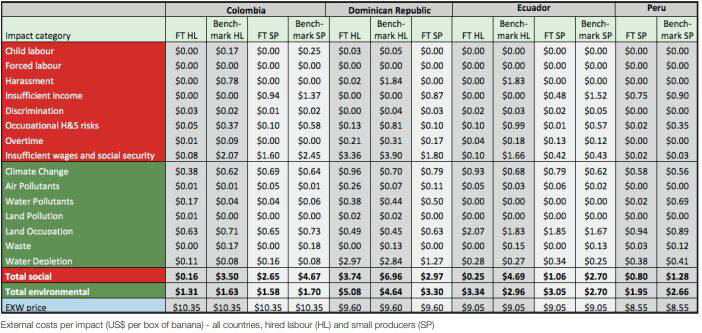

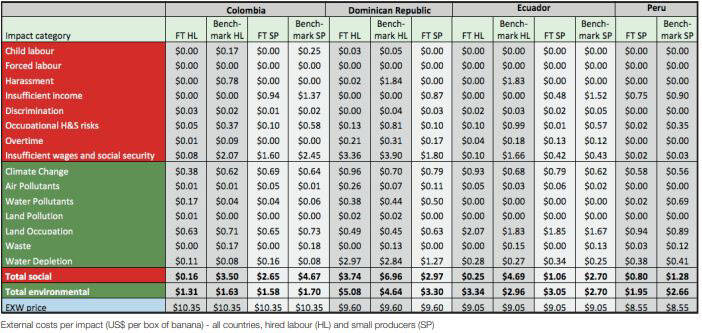

Social costs is an umbrella term including inequality in labor conditions. What would a product cost if it was produced without child or slave labor, for fair wages in safe conditions? Social costs also include racial or gender inequality, and any other societal issues standing in the way of equal rights to a good and dignified life for all.

Environmental costs include the toll production and distribution takes on our planet. Environmental costs include carbon emissions, air pollution, soil erosion, deforestation, loss of biodiversity, animal welfare, and other factors of the reality of climate change.

Domestic tourism will recover faster

True Price is turning into a genuine movement. A growing number of farmers and businesses are advocating for increasing transparency and revealing hidden costs. But what are these costs? How do you calculate the true price of food? At the True Price store in Amsterdam, the first of its kind in the world, they summarize the calculation like this: True Price = retail price plus social costs plus environmental costs

The hidden costs of a global food system

true price

Jelle Steenbergen Wouter Noordijk

The price we’re used to paying for the food we love does not reflect reality. The food system as we built it during the 20th century was heedless or ignorant of the social and environmental costs associated with the product. The race to the bottom left a wake of inequity that we’re only now beginning to wake up to. The massive disruption caused by the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic is the perfect time to reevaluate the true price of our food, the price that we must be willing to pay to ensure a fair future of food. A short and transparent supply chain by means of relocalization is an excellent starting point for exposing and taking charge of the hidden costs associated with our food production.

trendwatch

4 min

true price

© Chantal Arnts

True Price Michel Scholte

What’s the goal?

Founder of True Price Michel Scholte: “The goal isn’t to charge higher prices. The goal is to develop products with a lower societal and environmental cost.” Asking consumers to pay more for the same product is a tough sell in the best of times, and we are not in the best of times. With food inequality on the rise due to the COVID-19 pandemic, asking consumers to pay a true price is beyond the means of many.

Continuing to be willfully ignorant of external costs will, however, lead to more problems down the road. The process of internalizing these external costs may be long and painful, and the brunt of the burden will need to be carried by those that have the means to do so. Corporations have begun to pivot towards a broader purpose, in which they are no longer beholden to shareholder value above everything. True price calculations should be part of this new wave and definition of economic growth. The hard reality is that short term profits will need to be sacrificed for long term gains, and that if you can afford to do so, you should consider paying a little more for the food you love, so that the people that can’t might be able to in the future.

Example of True Price calculation

Retail price for a chocolate bar of 100 grams: 1,45 dollars

True Price: 1.94 dollars

The difference of 0,49 dollars between retail price and True Price is mainly caused by the unfair wages of coffee farmers (social price) and pollution from transport (natural price).

Retail price a liter of milk from a Dutch farmer: 1.39 dollars

True Price: 1,69 dollars

The difference of 0.30 cents caused partially by low wages and the unfair competitive position of supermarkets in comparison to farmers in the Netherlands (social price). For the most part the difference between True Price and retail price is caused by the price of land use and emissions caused cows (natural price).

It should be noted that these methods are far from complete or comprehensive. Further research and modeling is needed to ensure a more accurate reflection of reality.

© Chantal Arnts

Restoration costs. These are the costs of bringing people’s health, wealth, circumstances, capabilities, or environmental stocks and environmental qualities to the state they would have been in the absence of the social and environmental damage associated with an impact. Replanting a forest would be an example, as would raising the wages of workers to a fair living standard.

Compensation costs. These are applied when the social or economic damage of an impact is severe or long lasting enough to require compensation. To continue with the example above, these would include back-pay for the workers, and expanding replanting efforts to compensate for the carbon absorption lost from deforestation.

Prevention of recurrence costs. These represent the costs that would be incurred in the future to avoid, avert or prevent the identified social and environmental impacts of a product from occurring again. For example putting an independent analyst in place to prevent human rights breaches from occuring again, or similarly a forestry service or other protective measures.

Retribution costs. The costs associated with fines, sanctions or penalties imposed by governments for certain violations of legal or widely accepted obligations. They represent the damage to society caused by breaking the law.

The question that then rises is how to calculate these significant and broad external costs? Sticking with the methods used by the True Price foundation they identify four different principles to include in their monetization factors, taken from the comprehensive paper released by the True Price Foundation:

Koeckebackers

The retail price is the price we’re used to paying, and takes into account the economic and market forces, as well as traditional profit margins.

Social costs is an umbrella term including inequality in labor conditions. What would a product cost if it was produced without child or slave labor, for fair wages in safe conditions? Social costs also include racial or gender inequality, and any other societal issues standing in the way of equal rights to a good and dignified life for all.

Environmental costs include the toll production and distribution takes on our planet. Environmental costs include carbon emissions, air pollution, soil erosion, deforestation, loss of biodiversity, animal welfare, and other factors of the reality of climate change.

Domestic tourism will recover faster

True Price is turning into a genuine movement. A growing number of farmers and businesses are advocating for increasing transparency and revealing hidden costs. But what are these costs? How do you calculate the true price of food? At the True Price store in Amsterdam, the first of its kind in the world, they summarize the calculation like this: True Price = retail price plus social costs plus environmental costs

The hidden costs of a global food system

true price

Jelle Steenbergen Wouter Noordijk

The price we’re used to paying for the food we love does not reflect reality. The food system as we built it during the 20th century was heedless or ignorant of the social and environmental costs associated with the product. The race to the bottom left a wake of inequity that we’re only now beginning to wake up to. The massive disruption caused by the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic is the perfect time to reevaluate the true price of our food, the price that we must be willing to pay to ensure a fair future of food. A short and transparent supply chain by means of relocalization is an excellent starting point for exposing and taking charge of the hidden costs associated with our food production.

4 min