Cycling back to this magazine’s theme, it’s becoming clear that the solution of upcycling food is both part of a greater whole, and a microcosm of the unseen benefits fighting climate change can bring. If even our waste can be turned into some of the many beautiful things we showcase in the coming pages, why should we not be hopeful for the future? Our literal waste can be shaped into the building blocks of a better world, so next time you throw something out, try to think of what could be. If we all do that, we just might get there.

Solving the climate crisis is often painted in such a way as to require great sacrifices from ordinary people. You have to change the way you live and do business, and it’s going to be uncomfortable. And while that’s true, wouldn’t it be better to focus on the many co-benefits of climate solutions? Yes, we have to change, but it’s a change for the better. Most climate solutions are quite literally about building a better, more sustainable, and more equitable world. Reduced air pollution means better public health. Regenerative farming means increased biodiversity. Radical change means the possibility to do radically better. Even the financial case is clear. Research estimates implementing climate solutions would cost us nearly 30 trillion US dollars, an unfathomable amount of money only eclipsed by the potential 145 trillion dollars in savings. And those estimates don’t include the previously mentioned co-benefits.

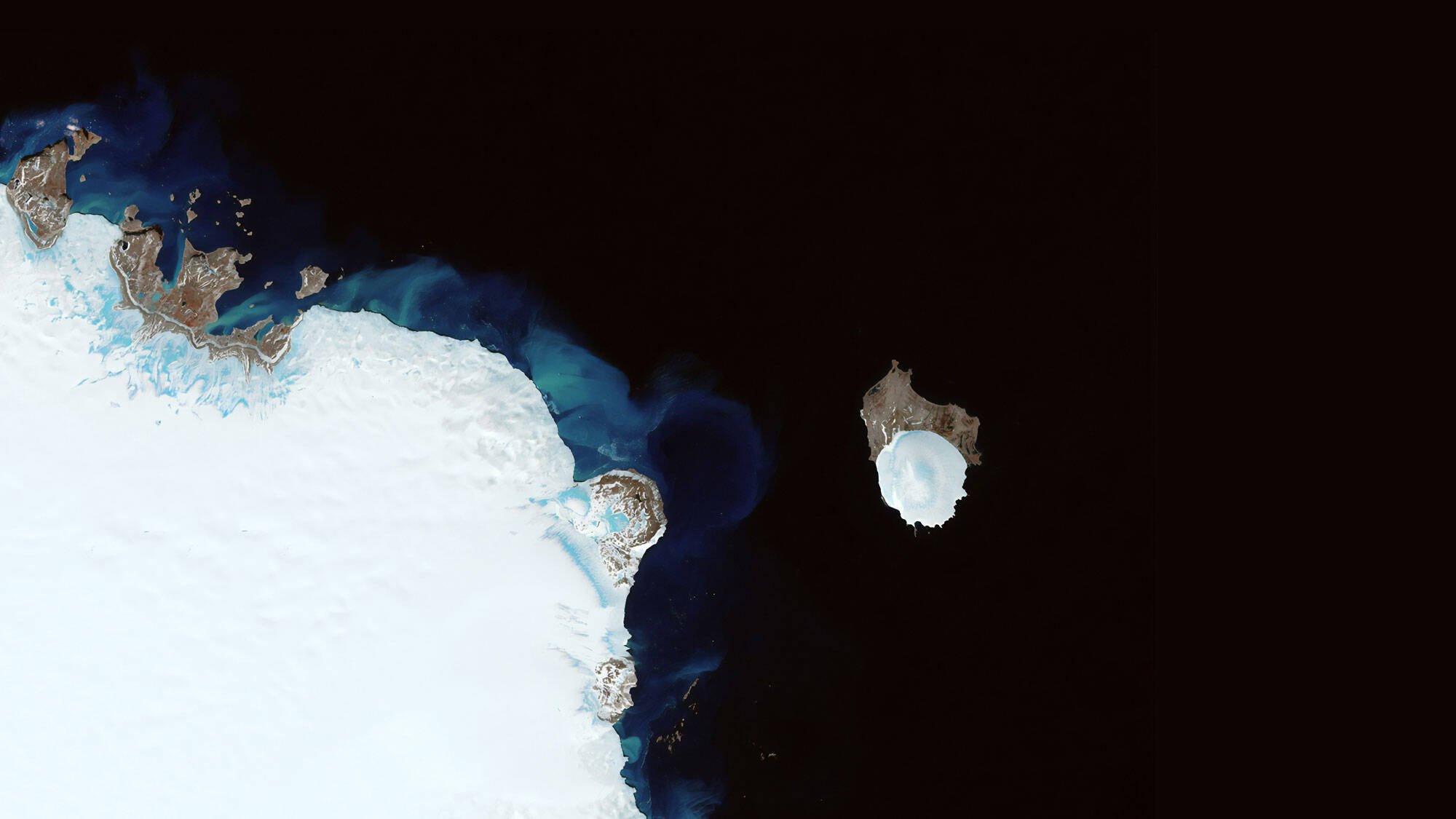

Contributing to climate solutions can often feel like a drop in the ocean, especially on the household level. Sure, in high-income countries we throw away on average 35 percent of food on the household level, but compared to gigatons we need to make a difference. Individual action tends to feel less impactful. It’s easy to despair, but that’s why it’s important to stay focused on the solutions instead of the problems. If we manage to successfully scale the climate solutions we already have available to us, we can reach the point of drawdown, wherein the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere begins to go down instead of up, by the middle of this century. That’s reason to hope.

In a gross simplification of the problem, more room for nature is generally better. Maximizing our use of natural resources creates more room for nature to do its thing, and creates less waste. Ideally, we would be producing exactly the amount of food we need, but until we get to that distant goal, making sure our excesses don’t cause further harm is the next best thing. That’s the essence of the circular economy in food, and upcycling can be a vital part of that. If we can make textiles out of orange fibers or shellfish chitin, then perhaps a cotton field could be turned into a forest. The FAO statistic that we waste a third of all the food we produce has been quoted to death, but what if we turned that third into something else edible or useful? Suddenly we’d need 33 percent less land. Imagine what we could use that land for with a focus on climate solutions.

Make no mistake, solving food waste is perhaps the most impactful solution to climate change. The scientists at Project Drawdown, a renowned and leading resource on climate solutions, estimate that reducing food waste by 50 percent by 2050 would lead to 87.4 gigatons less carbon emissions by 2050, more than any other individual solution. In the initial Drawdown estimates from 2017, food waste accounted for 70.5 gigatons. The bulk of those potential savings is from reduced deforestation to create additional farmland, and it’s exactly those kinds of knock-on effects that upcycling food can make a difference in.

If we want to solve the climate crisis, upcycling food is just a small step on a long road. Upcycling food helps reduce food waste, which in turn is one of dozens of climate solutions we need to implement to safeguard the future of people on our planet.

Jelle Steenbergen Xiao Er Kong

essay

3 min

part of a greater whole

Cycling back to this magazine’s theme, it’s becoming clear that the solution of upcycling food is both part of a greater whole, and a microcosm of the unseen benefits fighting climate change can bring. If even our waste can be turned into some of the many beautiful things we showcase in the coming pages, why should we not be hopeful for the future? Our literal waste can be shaped into the building blocks of a better world, so next time you throw something out, try to think of what could be. If we all do that, we just might get there.

Solving the climate crisis is often painted in such a way as to require great sacrifices from ordinary people. You have to change the way you live and do business, and it’s going to be uncomfortable. And while that’s true, wouldn’t it be better to focus on the many co-benefits of climate solutions? Yes, we have to change, but it’s a change for the better. Most climate solutions are quite literally about building a better, more sustainable, and more equitable world. Reduced air pollution means better public health. Regenerative farming means increased biodiversity. Radical change means the possibility to do radically better. Even the financial case is clear. Research estimates implementing climate solutions would cost us nearly 30 trillion US dollars, an unfathomable amount of money only eclipsed by the potential 145 trillion dollars in savings. And those estimates don’t include the previously mentioned co-benefits.

Contributing to climate solutions can often feel like a drop in the ocean, especially on the household level. Sure, in high-income countries we throw away on average 35 percent of food on the household level, but compared to gigatons we need to make a difference. Individual action tends to feel less impactful. It’s easy to despair, but that’s why it’s important to stay focused on the solutions instead of the problems. If we manage to successfully scale the climate solutions we already have available to us, we can reach the point of drawdown, wherein the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere begins to go down instead of up, by the middle of this century. That’s reason to hope.

In a gross simplification of the problem, more room for nature is generally better. Maximizing our use of natural resources creates more room for nature to do its thing, and creates less waste. Ideally, we would be producing exactly the amount of food we need, but until we get to that distant goal, making sure our excesses don’t cause further harm is the next best thing. That’s the essence of the circular economy in food, and upcycling can be a vital part of that. If we can make textiles out of orange fibers or shellfish chitin, then perhaps a cotton field could be turned into a forest. The FAO statistic that we waste a third of all the food we produce has been quoted to death, but what if we turned that third into something else edible or useful? Suddenly we’d need 33 percent less land. Imagine what we could use that land for with a focus on climate solutions.

Make no mistake, solving food waste is perhaps the most impactful solution to climate change. The scientists at Project Drawdown, a renowned and leading resource on climate solutions, estimate that reducing food waste by 50 percent by 2050 would lead to 87.4 gigatons less carbon emissions by 2050, more than any other individual solution. In the initial Drawdown estimates from 2017, food waste accounted for 70.5 gigatons. The bulk of those potential savings is from reduced deforestation to create additional farmland, and it’s exactly those kinds of knock-on effects that upcycling food can make a difference in.

If we want to solve the climate crisis, upcycling food is just a small step on a long road. Upcycling food helps reduce food waste, which in turn is one of dozens of climate solutions we need to implement to safeguard the future of people on our planet.

Jelle Steenbergen Xiao Er Kong

3 min