Which version of this classic Dutch Oliebol would you rather eat?

Better lights make for better meals

You come across a frozen pizza in the supermarket, lit by the cold, harsh light of the freezer. You walk past it without giving it a second thought. The next time you’re at the supermarket the lights in the freezer have been replaced with warm yellow instead of chilly blue, and the pizza suddenly looks a lot better. Sound plausible? It is, according to an early exploratory study. Good lighting isn’t just important for photographers, but also for stores. Rich, warm lights make the exact same packaged food seem tastier and of higher quality. This seems like it could be a wake-up call for most supermarkets, and possibly worth considering for product developers. Whether this is a real effect or ‘one neat trick that will amaze you’ remains to be seen, but if research is showing we eat with our eyes it seems worth it to make sure our eyes have something to feast on.

How much would you pay for this incredible piece of art by chef Jonnie Boer? (by Apicbase.com)

Plating matters

This one we secretly knew already, but it helps to have science back you up on it. In short: people are willing to pay more for expertly plated dishes. Artistically arranged appetizers command a higher price than an unremarkable heap on the plate. Also, the center of the plate is where the magic happens. An incredible arrangement off to the side is less effective than an identical placement smack dab in the middle of the exact same place. People really do eat with their eyes.

Interestingly, if you have people reach for a ‘small’ flavor while tasting a ‘large’ flavor there’s no significant interference.

Flavors have a size

We’re not talking about richness or presence in a dish here, but an association of actual physical size. This sounds stranger than it really is, because it’s a logical connection between a flavor and where we assume it comes from. An orange — to stay in the fruit space — tastes bigger than a strawberry, because an orange is bigger than a strawberry. How do you even measure this? Well, if you present someone with a ‘small’ flavor while at the same time having them blindly grab hold of something associated with a ‘large’ flavor (i.e. feeding someone a strawberry while having them blindly reach for an orange), most people will move their hands as if to pick up a strawberry first. Practical applications seem limited to niche dinner-in-the-dark type situations, but these types of incongruences open the door to creative approaches to food.

Umami looks to be immune to this effect. While maybe not immediately obvious, this might be the most important takeaway. Specifically for foodservice on airplanes or long distance trains. Umami-rich dishes are a lot easier to get right in extreme circumstances.

If you instead want to emphasize the bitterness, you might consider pumping up the bass.

Serving dessert? Go for high notes and light instruments. These enhance the perception of sweetness.

27% of all drink orders on airplanes are tomato juice, with or without alcohol. Why? Partly because umami doesn’t care about noise.

Background music influences flavor perception

Does a meal in a loud restaurant taste differently because it’s so loud? The answer is possibly yes. Enough that the acoustics of a dining experience should be a serious consideration, and a possible source of untapped potential. Several studies have been done on this, though the field of gastrophysics is still emerging. We’ve drawn a few practical conclusions for you:

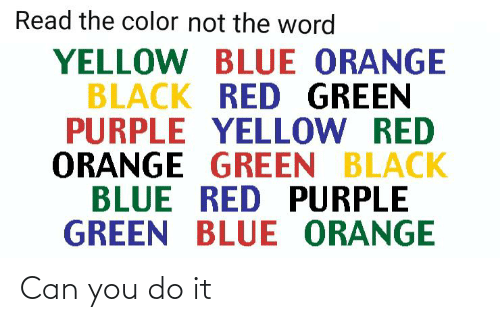

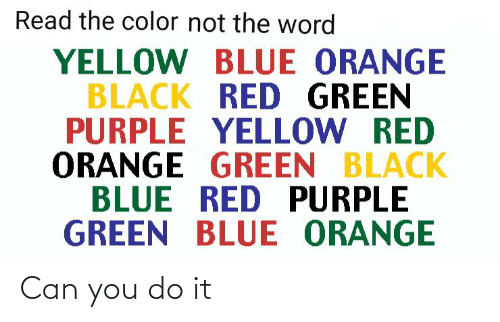

This (in)famous experiment was first conducted by John Ridley Stroop all the way back in 1935

Tasting helps you process language

You’ve probably heard of the experiment where you’re presented with the definition of a color, in a different color. If that doesn’t make sense, it’s like this: yellow, red, green. The trick is to answer what color you’re seeing as fast as possible. In this comparison we’re talking about two competing visual stimuli, but it also provides some interesting results when combining flavor and language. For instance, you could eat a strawberry while presented with the word peach. This study also presented participants with incomplete words (e.g. st_aw_err_), and found that people correctly identified they were tasting strawberry faster than when they were given the whole word. The gustative stimuli triggered the spontaneous completion of incomplete words. In other words, tasting could help you process language. Maybe try a taco while trying to learn spanish?

The science of gastrophysics is still emerging. The past decade has seen a wealth of exploratory research and seemingly zany experiments with surprising results. We’ve listed a few for you. Are these mostly science for science’s sake, or will they turn out to have creative practical applications? Jury’s still out, but at least they’re interesting.

Jelle Steenbergen Xiao Er Kong

Is gastrophysics paving the way for a new wave of creativity in food?

Five interesting findings in flavor

trendwatch

6 min

five interesting findings in flavor

Finding 1:

Razumiejczyk, E., Macbeth, G., Marmolejo-Ramos, F., & Noguchi, K. (2015). Crossmodal integration between visual linguistic information and flavour perception. Appetite, 91, 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APPET.2015.03.035

Finding 2:

Crisinel, A., Cosser, S., King, S., Jones, R., Petrie, J. and Spence, C. (2012). A bittersweet symphony: Systematically modulating the taste of food by changing the sonic properties of the soundtrack playing in the background. Food Quality and Preference, 24(1), pp.201-204.

Crisinel, A. and Spence, C. (2010). As bitter as a trombone: Synesthetic correspondences in nonsynesthetes between tastes/flavors and musical notes. Attention, Perception & Psychophysics, 72(7), pp.1994-2002.

Piqueras-Fiszman, B. and Spence, C. (n.d.). Multisensory Flavor Perception: From Fundamental Neuroscience Through to the Marketplace. 1st ed. Duxford: Elsevier.

Woods, A., Poliakoff, E., Lloyd, D., Kuenzel, J., Hodson, R., Gonda, H., Batchelor, J., Dijksterhuis, G. and Thomas, A. (2011). Effect of background noise on food perception. Food Quality and Preference, 22(1), pp.42-47.

Yan, K. and Dando, R. (2015). A crossmodal role for audition in taste perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 41(3), pp.590-596.

Finding 3:

Parma, V., Ghirardello, D., Tirindelli, R., & Castiello, U. (2011). Grasping a fruit. Hands do what flavour says. Appetite, 56(2), 249–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APPET.2010.12.013

Finding 4:

Michel, C., Velasco, C., Fraemohs, P., & Spence, C. (2015). Studying the impact of plating on ratings of the food served in a naturalistic dining context☆Acknowledgements: CM is the Chef-in-residence at the Crossmodal Research Laboratory, University of Oxford. CV would like to thank COLFUTURO for part funding his PhD. CS would like to thank the AHRC who funded the ‘Rethinking the Senses’ project (AH/L007053/1).☆. Appetite, 90, 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APPET.2015.02.030

Finding 5:

Otterbring, T., Löfgren, M., & Lestelius, M. (2014). Let There be Light! An Initial Exploratory Study of Whether Lighting Influences Consumer Evaluations of Packaged Food Products. Journal of Sensory Studies, 29(4), 294–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/JOSS.12103

Which version of this classic Dutch Oliebol would you rather eat?

Better lights make for better meals

You come across a frozen pizza in the supermarket, lit by the cold, harsh light of the freezer. You walk past it without giving it a second thought. The next time you’re at the supermarket the lights in the freezer have been replaced with warm yellow instead of chilly blue, and the pizza suddenly looks a lot better. Sound plausible? It is, according to an early exploratory study. Good lighting isn’t just important for photographers, but also for stores. Rich, warm lights make the exact same packaged food seem tastier and of higher quality. This seems like it could be a wake-up call for most supermarkets, and possibly worth considering for product developers. Whether this is a real effect or ‘one neat trick that will amaze you’ remains to be seen, but if research is showing we eat with our eyes it seems worth it to make sure our eyes have something to feast on.

How much would you pay for this incredible piece of art by chef Jonnie Boer? (by Apicbase.com)

Plating matters

This one we secretly knew already, but it helps to have science back you up on it. In short: people are willing to pay more for expertly plated dishes. Artistically arranged appetizers command a higher price than an unremarkable heap on the plate. Also, the center of the plate is where the magic happens. An incredible arrangement off to the side is less effective than an identical placement smack dab in the middle of the exact same place. People really do eat with their eyes.

Interestingly, if you have people reach for a ‘small’ flavor while tasting a ‘large’ flavor there’s no significant interference.

Flavors have a size

We’re not talking about richness or presence in a dish here, but an association of actual physical size. This sounds stranger than it really is, because it’s a logical connection between a flavor and where we assume it comes from. An orange — to stay in the fruit space — tastes bigger than a strawberry, because an orange is bigger than a strawberry. How do you even measure this? Well, if you present someone with a ‘small’ flavor while at the same time having them blindly grab hold of something associated with a ‘large’ flavor (i.e. feeding someone a strawberry while having them blindly reach for an orange), most people will move their hands as if to pick up a strawberry first. Practical applications seem limited to niche dinner-in-the-dark type situations, but these types of incongruences open the door to creative approaches to food.

Umami looks to be immune to this effect. While maybe not immediately obvious, this might be the most important takeaway. Specifically for foodservice on airplanes or long distance trains. Umami-rich dishes are a lot easier to get right in extreme circumstances.

If you instead want to emphasize the bitterness, you might consider pumping up the bass.

Serving dessert? Go for high notes and light instruments. These enhance the perception of sweetness.

27% of all drink orders on airplanes are tomato juice, with or without alcohol. Why? Partly because umami doesn’t care about noise.

Background music influences flavor perception

Does a meal in a loud restaurant taste differently because it’s so loud? The answer is possibly yes. Enough that the acoustics of a dining experience should be a serious consideration, and a possible source of untapped potential. Several studies have been done on this, though the field of gastrophysics is still emerging. We’ve drawn a few practical conclusions for you:

This (in)famous experiment was first conducted by John Ridley Stroop all the way back in 1935

Tasting helps you process language

You’ve probably heard of the experiment where you’re presented with the definition of a color, in a different color. If that doesn’t make sense, it’s like this: yellow, red, green. The trick is to answer what color you’re seeing as fast as possible. In this comparison we’re talking about two competing visual stimuli, but it also provides some interesting results when combining flavor and language. For instance, you could eat a strawberry while presented with the word peach. This study also presented participants with incomplete words (e.g. st_aw_err_), and found that people correctly identified they were tasting strawberry faster than when they were given the whole word. The gustative stimuli triggered the spontaneous completion of incomplete words. In other words, tasting could help you process language. Maybe try a taco while trying to learn spanish?

The science of gastrophysics is still emerging. The past decade has seen a wealth of exploratory research and seemingly zany experiments with surprising results. We’ve listed a few for you. Are these mostly science for science’s sake, or will they turn out to have creative practical applications? Jury’s still out, but at least they’re interesting.

Jelle Steenbergen Xiao Er Kong

Is gastrophysics paving the way for a new wave of creativity in food?

Five interesting findings in flavor

6 min