Food activists who keep ancient food culture and knowledge alive

From traditional techniques to heritage crops

Choices around food have an impact on the future of the planet. From the first colonization and then via globalization, many social demographic and economic shifts have occurred. These have caused a depopulation of rural and mountain areas, and gave rise to additional challenges. In recent years, we have also been faced with the loss of biodiversity and healthy soil, principally due to the industrialization of food production worldwide. Much of the ancient knowledge around holistic food production has been lost, while systems that are more natural could become part of the solution to a healthier food system.

Worldwide, more and more individuals and organizations are acknowledging the importance of indigenous and ancient culinary traditions. Food Inspiration highlights five examples dedicated to creating awareness and keeping indigenous and ancient food culture and knowledge alive.

Lisa Appels Courtesy of the organizations portrayed Loraine Elemans

EDITORIAL

11 min

The Ghana Food Movement is an organization that aims to heighten awareness of Ghanaian cuisine around the world. The movement supports initiatives that work toward a healthy food system in Ghana. The network currently consists of approximately 100 members, called movers; they include farmers, scientists, chefs, journalists, policy makers, entrepreneurs, and producers.

The Ghana Food Movement was founded by the Dutch food entrepreneur Lotte Wouters, who moved to the West African country with her family in 2018. Wouters had never lived in West Africa before, but was immediately touched by the incredible variety of dishes, food producers, and their stories. In Europe, organizations that connect food professionals with each other are the norm, but in Ghana there was no such infrastructure.

The Ghana Food Movement takes a different approach by opening their own test kitchen where food producers, chefs and start-ups work together. Wouters: “In that kitchen we’ll train young people to become product developers. We will teach them how to add value to local products. We will also offer young chefs and start-ups a place to grow. And, most importantly, we don't just want to reinvent the kitchen, we also want to celebrate what we have here and ensure that the traditional Ghanaian food culture is not lost.”

"The media in the Global North often conveys that people in Africa are starving. But that’s not the case at all; there is food in abundance here. Because of this misinformation, nonprofit organizations come to Ghana, supposedly to help the population. One example of this is a prominent organization that wants to eliminate hunger and improve living standards of farmers in developing countries. For years, this organization has invested heavily in the production of 'safe mono products' in Ghana, like corn and soy. This has had dramatic consequences. There has been a total disregard of what is needed and effective in this culture. In the old days, many farmers here worked with multiple business models and produced different types of crops, to mitigate risk. But because of the organization’s highly subsidized cropping program, they started to focus on monoculture and thus on producing only one crop. Their multi-entrepreneurship approach has been eroded completely, resulting in much higher risks. So, when a crop fails, the entire annual turnover is lost."

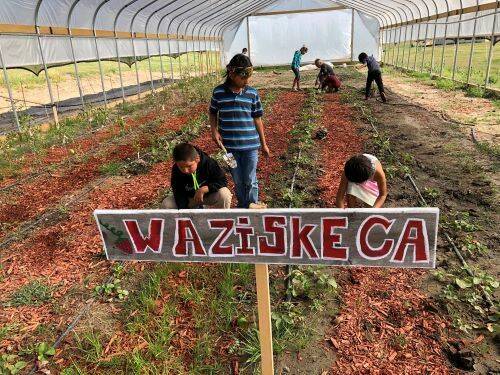

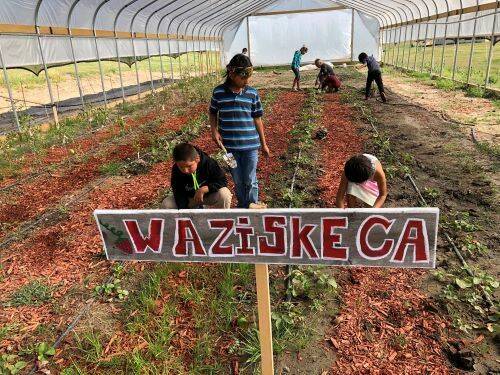

The First Nations Development Institute works to improve economic conditions for Native Americans through technical assistance and training, advocacy and policy, and direct financial grants.

After multiple generations of reliance on a particular food system, many indigenous communities adapted to the plants and animals found in their homelands. In the last century, this intimate relationship with the landscape has been violently disrupted due to colonization and globalization, and alarming rates of environmental degradation. Removed from their lands and forced to assimilate into the so-called “mainstream” culture, many native people no longer live in their traditional territories, nor do they eat their traditional foods. Today, many traditional foods are on the verge of extinction. The traditional knowledge of how to utilize and prepare certain traditional foods has been severely diminished.

“I think I have the best job in the world because all I do is work with indigenous food projects all across the mainland United States, Alaska and Hawaii. Each has its own unique positioning with distinctive issues. Everyone knows about Standing Rock, but every indigenous community has a similar story. I don't think there's one community that hasn't had to fight for their water or their land or their seeds or their people. In Standing Rock, they've had a long-established food project where they work with elder, indigenous food keepers, people who know about Lakota, Dakota Nakota food systems, and they pair them up with young people. It's a system of passing down indigenous knowledge about the area.”

In an ideal world - according to Romero-Briones - indigenous communities would be thriving, could take care of their homelands and be able to speak their indigenous language. "This country has so many microclimates. There are more beyond our borders. I can guarantee there's an indigenous community that has adjusted and created cultural practices, behavior, and society stewardship that responds to that microenvironment. And really, that's what we need. We don't need blanket policies that apply from one coast to the other that offer little nuance in how the different climates operate, much less how the different communities operate in them.”

Despite these setbacks, indigenous people around the world are finding unique and innovative ways to adapt and revitalize their foodways on reservations, on public land, in rural parks, and in urban gardens. A-dae Romero-Briones is Director of Programs for the Native Food and Agricultural Program for First Nations Development Institute.

In the Manabí province on Ecuador's Pacific coast, Project Iche brings together a culinary school, restaurant, and a food lab under one roof. The initiative aims to impart ancient culinary traditions to a new generation of Ecuadorian chefs and curious diners, while also empowering the local community and creating a stronger economy.

Project Iche began as a response to rebuild Manabí, after the devastating earthquake that shook the region in 2016, by using food as a catalyst for growth. If there is one thing that unites the Manabitan people, it’s food. At Iche, they are bringing together tradition and innovation. The project touches on food in a myriad of ways: from growing vegetables and fresh herbs in the garden, to serving dishes in the restaurant. From product development in the laboratory, to teaching young chefs new skills and ancient cooking techniques, the project captures ancestral knowledge and recipes that until now, have primarily been conveyed by oral tradition.

Valentina Álvarez is one of the teachers and Chef the Cuisine at Iche Project: “We have four main ingredients that you will find in many of our recipes: peanuts, creole corn, sea salt and achiote. For me the best place in any house is the Manabita oven, a hemispherical clay pit topped by a removable grill. The oven can serve as a tandoor, stove, or grill. It can be used for various cooking techniques, like smoking, slow-cooking, dehydrating and fermenting. This traditional oven is not only for cooking, but also the place to share secrets, traditions and techniques, because up until now there are no books that can teach you.” The use of this ancestral type of oven from Manabí province is just one of many culinary traditions that Iche aims to both preserve and build on.”

The Iche School of Food and Hospitality bases its teaching method on a learning-by-doing philosophy. Students spend half of their time in theoretical training, and the other half in hands-on practice that allows them to apply newly acquired knowledge. In the morning, they study; in the afternoon they work in Iche’s restaurant and bar.

Lelani Lewis is chef, food stylist, self-proclaimed food activist and the creator of Code Noir, a cookbook and dinner series around the effects of colonialism on Caribbean cuisine.

Lewis: “Almost every Dutch person knows the famous painting ‘The Potato Eaters’ by Vincent van Gogh; an image immediately associated with Dutch food culture. However, potatoes originally are not from Europe, but from South America. We rarely consider the complex origin of the food on our plates.”

According to Lewis, there is much room for improvement in the food world. The definitions of cultural appropriation in food are still unclear for many. Culinary cultures are not set in stone. Products perceived to be authentic for a particular culture often are not. Lewis: “Across the centuries, there has been so much cross-pollination of recipes and ingredients. Did you know coconuts are not Caribbean by origin? They were brought along in large numbers by European explorers as provisions on their ships. To me, the fact that most culinary cultures are characterized by products of different heritage also contains some sort of beauty, despite its dark history. It clashes with the idea that we all have some sort of fixed, own culinary culture. In reality, we are all mixed.”

With the dinners and workshops she hosts under the name Code Noir, Lewis wants to emphasize the culinary heritage of the Caribbean. “When we consider food culture, we often relate this with positive aspects such as diversity, richness in flavors and a space for cultural interaction. I am convinced that food brings people together, but we must be conscious of the history behind different food cultures. In that history, there are also painful subjects like colonization, slavery and (forced and voluntary) migration. I wanted to create experiences in which guests acquire a better understanding of the cultural and colonial heritage of worldwide trade routes and the effects on the Caribbean cuisine and culture. The name Code Noir is directly inspired by ‘Le Code Noir,’ a decree that defined conditions of slavery in the French colonial empire.

To ensure the quality of Wildfarmed crops, the company has set specific standards for farmers that produce under their name, which revert back to techniques that were used before the industrialization of agriculture. For example, crops that are grown under the Wildfarmed name should be grown with companion plants, or as bi- or poly-crops, like beans, peas and oats. Farmers that are connected to Wildfarmed bring livestock to graze on overwintered cereals or cover crops to recycle nutrients as an important contribution to soil biology.

Wildfarmed is a UK-based company that offers a route to market for crops grown on farms that prioritize soil health. They work with farmers that embrace regenerative farm practices to improve biodiversity and soil health.

Wildfarmed isn’t just a group of farmers. The company grew to become the supplier of flour, grains, wines and other fresh produce, which is used at multiple hip and trendy restaurants and bakeries throughout the UK. The label now falls under the Wildfarmed Group; in bakeries, grains from Wildfarmed's farmers are made into breads and pastries. At Jolene restaurant in London, the grains are used to make fresh pasta. In addition, Wildfarmed owns a natural wine bar in London that serves wines made from grapes from Wildfarmed farmers' vineyards. Each Wildfarmed location seems unique and standalone, while in the end they are all part of the same food group.

Wildfarmed allows farmers to choose cereal varieties that are suitable for low input systems. According to Wildfarmed, with varieties that are both old and new, heritage grains are only part of the answer to the problem they are trying to solve, as they’re trying to help farmers adopt low input, biodiverse farming systems at scale. This requires varieties of grains that can thrive in these low input systems, so these can be cereals from 1320 till 2023.

According to the founders of Wildfarmed, we have replaced biology in conventional farming, which is integral to a healthy farming cycle, and substituted it with agro-chemistry, which is disadvantageous for the system in the long term. One of the co-founders of Wildfarmed is Andrew Derek Cocup Sr, also known as Andy Cato, an English musician, who is half of the electronic music duo, Groove Armada. His interest in farming began more than 15 years ago, after reading an article on the dire state of the industrial food system. “One line stuck: ‘If you don’t like the system, don’t depend on it’. That’s when I decided to try my hand at growing food. The first time I walked down to the greenhouse and saw the seeds that had sprouted, it was a revelation. When this became food on the table for my family, it changed my life,” he once told Mob Media.

The choices around food have an impact on the future of the planet. First colonization and then globalization, have caused many social demographic and economic shifts. They have caused depopulation of rural and mountain areas and gave rise to many more challenges. In recent years we have been faced with the loss of biodiversity and healthy soil, mainly due to the industrialization of food production worldwide. A lot of ancient knowledge around holistic food production is lost, while systems that are more natural could form part of the solution to a healthier food system.

From traditional techniques to heritage crops

Lisa Appels Courtesy of the organizations portrayed Loraine Elemans

Worldwide, more and more individuals and organizations are acknowledging the importance of indigenous and ancient culinary traditions. Food Inspiration highlights five examples dedicated to creating awareness and keeping indigenous and ancient food culture and knowledge alive.

Food activists who keep ancient food culture and knowledge alive

11 min

The Ghana Food Movement takes a different approach by opening their own test kitchen where food producers, chefs and start-ups work together. Wouters: “In that kitchen we’ll train young people to become product developers. We will teach them how to add value to local products. We will also offer young chefs and start-ups a place to grow. And, most importantly, we don't just want to reinvent the kitchen, we also want to celebrate what we have here and ensure that the traditional Ghanaian food culture is not lost.”

"The media in the Global North often conveys that people in Africa are starving. But that’s not the case at all; there is food in abundance here. Because of this misinformation, nonprofit organizations come to Ghana, supposedly to help the population. One example of this is a prominent organization that wants to eliminate hunger and improve living standards of farmers in developing countries. For years, this organization has invested heavily in the production of 'safe mono products' in Ghana, like corn and soy. This has had dramatic consequences. There has been a total disregard of what is needed and effective in this culture. In the old days, many farmers here worked with multiple business models and produced different types of crops, to mitigate risk. But because of the organization’s highly subsidized cropping program, they started to focus on monoculture and thus on producing only one crop. Their multi-entrepreneurship approach has been eroded completely, resulting in much higher risks. So, when a crop fails, the entire annual turnover is lost."

The Ghana Food Movement is an organization that aims to heighten awareness of Ghanaian cuisine around the world. The movement supports initiatives that work toward a healthy food system in Ghana. The network currently consists of approximately 100 members, called movers; they include farmers, scientists, chefs, journalists, policy makers, entrepreneurs, and producers.

The Ghana Food Movement was founded by the Dutch food entrepreneur Lotte Wouters, who moved to the West African country with her family in 2018. Wouters had never lived in West Africa before, but was immediately touched by the incredible variety of dishes, food producers, and their stories. In Europe, organizations that connect food professionals with each other are the norm, but in Ghana there was no such infrastructure.

The First Nations Development Institute works to improve economic conditions for Native Americans through technical assistance and training, advocacy and policy, and direct financial grants.

After multiple generations of reliance on a particular food system, many indigenous communities adapted to the plants and animals found in their homelands. In the last century, this intimate relationship with the landscape has been violently disrupted due to colonization and globalization, and alarming rates of environmental degradation. Removed from their lands and forced to assimilate into the so-called “mainstream” culture, many native people no longer live in their traditional territories, nor do they eat their traditional foods. Today, many traditional foods are on the verge of extinction. The traditional knowledge of how to utilize and prepare certain traditional foods has been severely diminished.

Despite these setbacks, indigenous people around the world are finding unique and innovative ways to adapt and revitalize their foodways on reservations, on public land, in rural parks, and in urban gardens. A-dae Romero-Briones is Director of Programs for the Native Food and Agricultural Program for First Nations Development Institute.

“I think I have the best job in the world because all I do is work with indigenous food projects all across the mainland United States, Alaska and Hawaii. Each has its own unique positioning with distinctive issues. Everyone knows about Standing Rock, but every indigenous community has a similar story. I don't think there's one community that hasn't had to fight for their water or their land or their seeds or their people. In Standing Rock, they've had a long-established food project where they work with elder, indigenous food keepers, people who know about Lakota, Dakota Nakota food systems, and they pair them up with young people. It's a system of passing down indigenous knowledge about the area.”

In an ideal world - according to Romero-Briones - indigenous communities would be thriving, could take care of their homelands and be able to speak their indigenous language. "This country has so many microclimates. There are more beyond our borders. I can guarantee there's an indigenous community that has adjusted and created cultural practices, behavior, and society stewardship that responds to that microenvironment. And really, that's what we need. We don't need blanket policies that apply from one coast to the other that offer little nuance in how the different climates operate, much less how the different communities operate in them.”

Valentina Álvarez is one of the teachers and Chef the Cuisine at Iche Project: “We have four main ingredients that you will find in many of our recipes: peanuts, creole corn, sea salt and achiote. For me the best place in any house is the Manabita oven, a hemispherical clay pit topped by a removable grill. The oven can serve as a tandoor, stove, or grill. It can be used for various cooking techniques, like smoking, slow-cooking, dehydrating and fermenting. This traditional oven is not only for cooking, but also the place to share secrets, traditions and techniques, because up until now there are no books that can teach you.” The use of this ancestral type of oven from Manabí province is just one of many culinary traditions that Iche aims to both preserve and build on.”

The Iche School of Food and Hospitality bases its teaching method on a learning-by-doing philosophy. Students spend half of their time in theoretical training, and the other half in hands-on practice that allows them to apply newly acquired knowledge. In the morning, they study; in the afternoon they work in Iche’s restaurant and bar.

Project Iche began as a response to rebuild Manabí, after the devastating earthquake that shook the region in 2016, by using food as a catalyst for growth. If there is one thing that unites the Manabitan people, it’s food. At Iche, they are bringing together tradition and innovation. The project touches on food in a myriad of ways: from growing vegetables and fresh herbs in the garden, to serving dishes in the restaurant. From product development in the laboratory, to teaching young chefs new skills and ancient cooking techniques, the project captures ancestral knowledge and recipes that until now, have primarily been conveyed by oral tradition.

In the Manabí province on Ecuador's Pacific coast, Project Iche brings together a culinary school, restaurant, and a food lab under one roof. The initiative aims to impart ancient culinary traditions to a new generation of Ecuadorian chefs and curious diners, while also empowering the local community and creating a stronger economy.

According to Lewis, there is much room for improvement in the food world. The definitions of cultural appropriation in food are still unclear for many. Culinary cultures are not set in stone. Products perceived to be authentic for a particular culture often are not. Lewis: “Across the centuries, there has been so much cross-pollination of recipes and ingredients. Did you know coconuts are not Caribbean by origin? They were brought along in large numbers by European explorers as provisions on their ships. To me, the fact that most culinary cultures are characterized by products of different heritage also contains some sort of beauty, despite its dark history. It clashes with the idea that we all have some sort of fixed, own culinary culture. In reality, we are all mixed.”

With the dinners and workshops she hosts under the name Code Noir, Lewis wants to emphasize the culinary heritage of the Caribbean. “When we consider food culture, we often relate this with positive aspects such as diversity, richness in flavors and a space for cultural interaction. I am convinced that food brings people together, but we must be conscious of the history behind different food cultures. In that history, there are also painful subjects like colonization, slavery and (forced and voluntary) migration. I wanted to create experiences in which guests acquire a better understanding of the cultural and colonial heritage of worldwide trade routes and the effects on the Caribbean cuisine and culture. The name Code Noir is directly inspired by ‘Le Code Noir,’ a decree that defined conditions of slavery in the French colonial empire.

Lelani Lewis is chef, food stylist, self-proclaimed food activist and the creator of Code Noir, a cookbook and dinner series around the effects of colonialism on Caribbean cuisine.

Lewis: “Almost every Dutch person knows the famous painting ‘The Potato Eaters’ by Vincent van Gogh; an image immediately associated with Dutch food culture. However, potatoes originally are not from Europe, but from South America. We rarely consider the complex origin of the food on our plates.”

Wildfarmed allows farmers to choose cereal varieties that are suitable for low input systems. According to Wildfarmed, with varieties that are both old and new, heritage grains are only part of the answer to the problem they are trying to solve, as they’re trying to help farmers adopt low input, biodiverse farming systems at scale. This requires varieties of grains that can thrive in these low input systems, so these can be cereals from 1320 till 2023.

According to the founders of Wildfarmed, we have replaced biology in conventional farming, which is integral to a healthy farming cycle, and substituted it with agro-chemistry, which is disadvantageous for the system in the long term. One of the co-founders of Wildfarmed is Andrew Derek Cocup Sr, also known as Andy Cato, an English musician, who is half of the electronic music duo, Groove Armada. His interest in farming began more than 15 years ago, after reading an article on the dire state of the industrial food system. “One line stuck: ‘If you don’t like the system, don’t depend on it’. That’s when I decided to try my hand at growing food. The first time I walked down to the greenhouse and saw the seeds that had sprouted, it was a revelation. When this became food on the table for my family, it changed my life,” he once told Mob Media.

Wildfarmed isn’t just a group of farmers. The company grew to become the supplier of flour, grains, wines and other fresh produce, which is used at multiple hip and trendy restaurants and bakeries throughout the UK. The label now falls under the Wildfarmed Group; in bakeries, grains from Wildfarmed's farmers are made into breads and pastries. At Jolene restaurant in London, the grains are used to make fresh pasta. In addition, Wildfarmed owns a natural wine bar in London that serves wines made from grapes from Wildfarmed farmers' vineyards. Each Wildfarmed location seems unique and standalone, while in the end they are all part of the same food group.

To ensure the quality of Wildfarmed crops, the company has set specific standards for farmers that produce under their name, which revert back to techniques that were used before the industrialization of agriculture. For example, crops that are grown under the Wildfarmed name should be grown with companion plants, or as bi- or poly-crops, like beans, peas and oats. Farmers that are connected to Wildfarmed bring livestock to graze on overwintered cereals or cover crops to recycle nutrients as an important contribution to soil biology.

Wildfarmed is a UK-based company that offers a route to market for crops grown on farms that prioritize soil health. They work with farmers that embrace regenerative farm practices to improve biodiversity and soil health.