“In the upcoming years I am looking to partner with more farmers, aggregators, fresh cut facilities, and big food companies to scale up what we're doing more quickly. There is so much food to reintegrate and reconnecting the pieces of a fragmented food system is what Matriark does – for the health of people and the planet. By working with diverse supply chains and companies with infrastructure capacities, we can make an enormous impact. It’s all about partnership and letting down traditional barriers of competition – that’s what it’s going to take to make the global change we need, and Matriark is on a mission to realize these changes."

“Since founding the company in 2018, we’ve grown a lot. We're now selling into large scale food service. We're working with some national and international fruit and vegetable companies on product development. And we have just made our first big sale to Chartwells, which is a Compass Group company that provides food for higher education. Also we just became a part of the Foodbuy Accelerator for minority and women-owned businesses. That's important because Foodbuy is the largest group purchasing organization in North America, which means that we will be able to sell in large quantities, across the United States. Which really means we can reduce food waste on a massive scale: one pallet of our broth concentrate, diverts 1500 pounds of vegetable waste.”

“Then there’s also the fact they have to change their processes, so that when they're peeling carrots, for example, or they're chopping the tops off of a bunch of celery, to capture those in the same way that they capture the celery sticks, and the carrot sticks that they're using themselves. It's a heavy lift for a big processing facility to make those changes. But in the end when they do, it serves them in multiple ways. Not just do we pay them for their by-product, they also don’t lose money on sending it to landfill or compost.”

“What’s challenging in scaling a food business and especially with a ground-breaking supply chain, are the logistics, rules and regulations around health, paperwork, traceability and transportation – all the things that keep food safe – and messy. Getting to the place we've gotten, while it seems like a radically simple idea, is actually extremely complex. Every supplier that we work with has to be willing to change a number of systems they have in place. In order for us to use some of their ‘waste’ they have to re-classify products which were formerly unclassified as food.”

“Making a vegetable broth in your home kitchen is very different from making it at an industrial scale. We started to experiment on a small scale, and after a while we developed a product that was delicious and a supply chain that was secure. We were able to work with a co-packer who really loved our idea. They have been working in the food business for over 20 years and they already saw market trends going in a more sustainable direction. They agreed to work with us despite our unconventional approach.”

“Early on, the first thing that I did was to assess the categories of vegetable waste; what’s being wasted most in New York State. I met a number of people who were doing data analysis of food surplus and waste. I also started looking at many food manufacturers, seeing enormous waste streams, in particular, at fresh cut facilities. The products we make, really came out of what was available. It is quite the opposite approach of most food companies, who for example decide to produce a vegan coconut celery kale ginger soup, after which they search for the products to make it. Our approach is more similar to the way a good chef or home cook goes about making something: they open the refrigerator, they ask themselves; what can I make from the stuff that’s in there. So when you see massive quantities of onions, carrots and celery going to waste, what's the most obvious thing to make: vegetable broth!”

“So in 2018 we started Matriark. The goal that we set is to upcycle farm surplus and fresh-cut remnants into healthy, delicious, low sodium vegetable products for schools, hospitals, food banks and other foodservice. We’ve really just kept very focused on our original impact proposition. That doesn’t happen often with startups, because they tend to start with one idea, and then find out that it's not working or what the market wants, and they shift to other concepts.”

“A couple of years ago I had the opportunity to go to India, with a Professor at NYU, who was teaching a food systems class. We visited one of the Akshaya Patra production facilities where the midday meals are produced for state run schools. The factory was built based on where it needed to be in order to get healthy food to children by 10:30 every morning. Every day, 65 thousand children are fed healthy, simple food using recyclable containers dropped off in electric cars, all in the traffic of Bangalore. I was just like; wow.. why can’t we do a version of that in the United States.”

“The program had a farm in upstate New York where we had a childrens learning garden during the summer. There were always just massive amounts of extra vegetables even just from a one acre space. Various food banks would come by to pick up surplus vegetables for redistribution. But no one could ever take more than a few boxes, because they didn't have proper storage. There was just no good infrastructure to get the food to places where it was needed. 40% of food is wasted in the United States, 1 in 9 people are food insecure, and 1 in 3 suffer from a diet-related illness. That’s insane. There’s an incredible dichotomy between people who need and want healthy food and incredible excess of food that is wasted, even in small ecosystems.”

“I started my career in the art world, but I decided to leave and explore a career in politics. That led me to a group of farmers in the county where I live, who were trying to create new policies around farmland, so they could produce food for the community. Eventually this led me to a position building a healthy eating program for youth and families living in public housing in New York City. One of the biggest barriers to eating healthy in a regular way is a terrible dearth of access to affordable fresh products.”

“Growing up, there was always fresh food in my household. My parents loved to prepare meals with very beautiful, fresh ingredients, simply cooked. We spent summers in Maine, very close to Eliot Coleman's first farm, one of the first organic farms in Maine, in the late 60s a beautiful place where we bought all of our vegetables and cooked with whatever was available. My mother was born in Prague and came to the US after World War II. Having lived through a war, she made sure there was never any waste in our family. That mentality has stuck with me all through my life.”

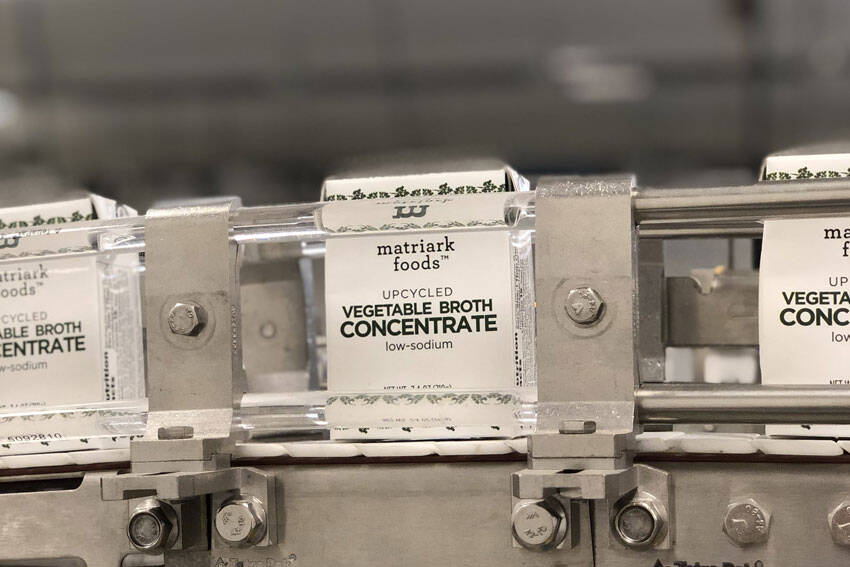

Matriark Foods upcycles food to create new products. Where others see waste they see a logistical challenge, a chance to protect the environment and a better way to feed communities. Their first product on the market is a vegetable broth concentrate. By sourcing imperfects and surplus from farmers and remnants from fresh-cut facilities, their Upcycled Broth Concentrate makes use of vegetables that would otherwise go to waste. Food Inspiration spoke with founder Anna Hammond.

Lisa Appels Matriark foods Xiao Er Kong

interview

7 min

has a bee ever sent you an invoice?

Anna Hammond

“In the upcoming years I am looking to partner with more farmers, aggregators, fresh cut facilities, and big food companies to scale up what we're doing more quickly. There is so much food to reintegrate and reconnecting the pieces of a fragmented food system is what Matriark does – for the health of people and the planet. By working with diverse supply chains and companies with infrastructure capacities, we can make an enormous impact. It’s all about partnership and letting down traditional barriers of competition – that’s what it’s going to take to make the global change we need, and Matriark is on a mission to realize these changes."

“Since founding the company in 2018, we’ve grown a lot. We're now selling into large scale food service. We're working with some national and international fruit and vegetable companies on product development. And we have just made our first big sale to Chartwells, which is a Compass Group company that provides food for higher education. Also we just became a part of the Foodbuy Accelerator for minority and women-owned businesses. That's important because Foodbuy is the largest group purchasing organization in North America, which means that we will be able to sell in large quantities, across the United States. Which really means we can reduce food waste on a massive scale: one pallet of our broth concentrate, diverts 1500 pounds of vegetable waste.”

“Then there’s also the fact they have to change their processes, so that when they're peeling carrots, for example, or they're chopping the tops off of a bunch of celery, to capture those in the same way that they capture the celery sticks, and the carrot sticks that they're using themselves. It's a heavy lift for a big processing facility to make those changes. But in the end when they do, it serves them in multiple ways. Not just do we pay them for their by-product, they also don’t lose money on sending it to landfill or compost.”

“What’s challenging in scaling a food business and especially with a ground-breaking supply chain, are the logistics, rules and regulations around health, paperwork, traceability and transportation – all the things that keep food safe – and messy. Getting to the place we've gotten, while it seems like a radically simple idea, is actually extremely complex. Every supplier that we work with has to be willing to change a number of systems they have in place. In order for us to use some of their ‘waste’ they have to re-classify products which were formerly unclassified as food.”

“Making a vegetable broth in your home kitchen is very different from making it at an industrial scale. We started to experiment on a small scale, and after a while we developed a product that was delicious and a supply chain that was secure. We were able to work with a co-packer who really loved our idea. They have been working in the food business for over 20 years and they already saw market trends going in a more sustainable direction. They agreed to work with us despite our unconventional approach.”

“Early on, the first thing that I did was to assess the categories of vegetable waste; what’s being wasted most in New York State. I met a number of people who were doing data analysis of food surplus and waste. I also started looking at many food manufacturers, seeing enormous waste streams, in particular, at fresh cut facilities. The products we make, really came out of what was available. It is quite the opposite approach of most food companies, who for example decide to produce a vegan coconut celery kale ginger soup, after which they search for the products to make it. Our approach is more similar to the way a good chef or home cook goes about making something: they open the refrigerator, they ask themselves; what can I make from the stuff that’s in there. So when you see massive quantities of onions, carrots and celery going to waste, what's the most obvious thing to make: vegetable broth!”

“So in 2018 we started Matriark. The goal that we set is to upcycle farm surplus and fresh-cut remnants into healthy, delicious, low sodium vegetable products for schools, hospitals, food banks and other foodservice. We’ve really just kept very focused on our original impact proposition. That doesn’t happen often with startups, because they tend to start with one idea, and then find out that it's not working or what the market wants, and they shift to other concepts.”

“A couple of years ago I had the opportunity to go to India, with a Professor at NYU, who was teaching a food systems class. We visited one of the Akshaya Patra production facilities where the midday meals are produced for state run schools. The factory was built based on where it needed to be in order to get healthy food to children by 10:30 every morning. Every day, 65 thousand children are fed healthy, simple food using recyclable containers dropped off in electric cars, all in the traffic of Bangalore. I was just like; wow.. why can’t we do a version of that in the United States.”

“The program had a farm in upstate New York where we had a childrens learning garden during the summer. There were always just massive amounts of extra vegetables even just from a one acre space. Various food banks would come by to pick up surplus vegetables for redistribution. But no one could ever take more than a few boxes, because they didn't have proper storage. There was just no good infrastructure to get the food to places where it was needed. 40% of food is wasted in the United States, 1 in 9 people are food insecure, and 1 in 3 suffer from a diet-related illness. That’s insane. There’s an incredible dichotomy between people who need and want healthy food and incredible excess of food that is wasted, even in small ecosystems.”

“I started my career in the art world, but I decided to leave and explore a career in politics. That led me to a group of farmers in the county where I live, who were trying to create new policies around farmland, so they could produce food for the community. Eventually this led me to a position building a healthy eating program for youth and families living in public housing in New York City. One of the biggest barriers to eating healthy in a regular way is a terrible dearth of access to affordable fresh products.”

“Growing up, there was always fresh food in my household. My parents loved to prepare meals with very beautiful, fresh ingredients, simply cooked. We spent summers in Maine, very close to Eliot Coleman's first farm, one of the first organic farms in Maine, in the late 60s a beautiful place where we bought all of our vegetables and cooked with whatever was available. My mother was born in Prague and came to the US after World War II. Having lived through a war, she made sure there was never any waste in our family. That mentality has stuck with me all through my life.”

Matriark Foods upcycles food to create new products. Where others see waste they see a logistical challenge, a chance to protect the environment and a better way to feed communities. Their first product on the market is a vegetable broth concentrate. By sourcing imperfects and surplus from farmers and remnants from fresh-cut facilities, their Upcycled Broth Concentrate makes use of vegetables that would otherwise go to waste. Food Inspiration spoke with founder Anna Hammond.

Lisa Appels Matriark foods Xiao Er Kong

7 min

Anna Hammond